"They Weren't Born Wanting to Do This"

Or: my thoughts on Charlie Kirk's murder

On Wednesday, conservative commentator Charlie Kirk was shot and killed while attending an event at Utah Valley University. I've been processing his death since then.

This death has hit me pretty hard, for a few reasons.

First: political commentating is a small group, and while I didn't know Charlie personally, we did have friends in common. Hearing those friends' pain has been heartbreaking.

But I think this also signals a dark moment for our country.

Political violence is, unfortunately and tragically, not new. As Amanda Ripley observed in Persuasion this July:

"Last week in Alvarado, Texas, ten people were charged with attempted murder after a police officer was shot in the neck outside an ICE detention center on July 4. In Minnesota last month, a man was charged with stalking and murdering state legislator Melissa Hortman and her husband before shooting and wounding state Senator John Hoffman and his wife. In April, Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro had to flee his burning home with his wife and children after an arson attack. In January, a man armed with a handgun made it past security and took a tour of the U.S. Capitol before being arrested. In the first five months of this year, according to the Threats and Harassment Dataset at the Bridging Divides Initiative, local officials reported more than 200 threats or harassment incidents. Meanwhile, threats against federal judges spiked in March and April, around the same time that President Donald Trump and his allies began blaming judges for blocking the administration’s agenda."

But for all that, it feels like Charlie's death represents the crossing of some invisible line. It is as though political violence is suddenly much worse in this country.

I think what it comes down to is this: as awful as it is when a politician is killed, political violence against a country's leaders has also been around since the dawn of time. Teddy Roosevelt was the victim of an assassination attempt. JFK was assassinated. Reagan was shot. This kind of violence is awful, but it's a kind of awful that we know.

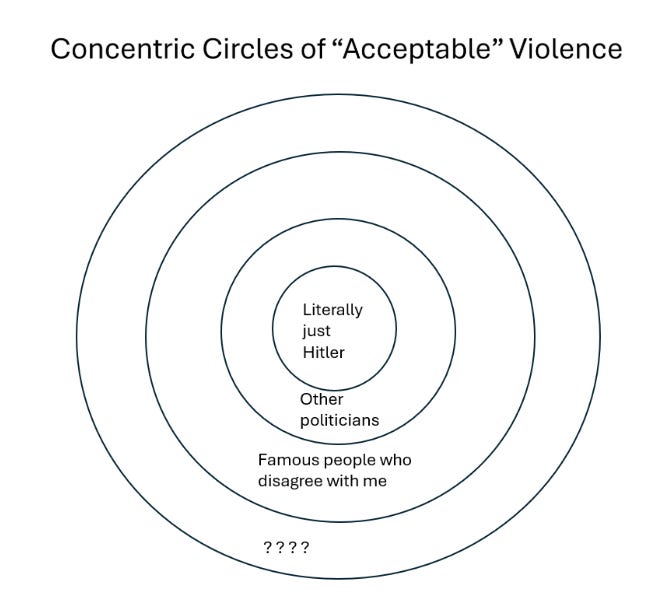

But killing unelected commentators simply for speaking their minds represents something new and, in my opinion, even more dangerous. It's as though the circle of what constitutes "acceptable" violence has just gotten bigger.

This is what I mean.

A healthy society lives in the smallest concentric circle in this diagram. If Hitler rose to power in this society, its people would rise up and kill him.

In the United States, we've usually lived somewhere in the second circle. Political violence against elected officials in our country has been historically very rare, but it has happened. We used to live near the inner edge of the second circle. In the last few years, as Ripley documents, we've been inching our way towards the outer edge.

But with Kirk's death, it feels like we're now firmly in circle three.

The commentators who I follow and talk to know it. After noting that he and Charlie spoke at the same events and were interviewed by the same TV hosts, Tangle head Isaac Saul wrote of Charlie's death that: "This could have been me."

One of my friends is scheduled to speak at a big event next month. This friend said that he'd be lying if he pretended, in the wake of Charlie's murder, that he hadn't thought about canceling his speech for his own safety.

Circle three is a terrifying place for a country to inhabit.

In Vox, Zack Beauchamp captured my crossing-the-Rubicon sense of this moment:

“In the past, the American democratic consensus has been strong enough to survive assassination attempts. Some, like the murder of Martin Luther King Jr., tested its bonds but didn’t break them. Others, like the assassination of John F. Kennedy Jr., may actually have strengthened them by creating a sense of shared grief and solidarity.

"But now the American political system is crumbling, and many of its tools for containing political violence lie shattered. This probably will not be the event to break America, but we have to consider the possibility that it may be.”

So where do we go from here?

The truth is that I'm not sure. I wish I had concrete answers.

But I've been thinking lately about permission structures, and I think maybe that holds a clue.

A permission structure, as I learned reading counterterrorism expert Elizabeth Neumann's excellent book Kingdom of Rage, is essentially which types of statements and actions are encouraged versus discouraged in a given community. In most of mainstream society, for instance, the permission structure around racism is clear: you don't suggest that one race is genetically better than another one. If you do, you get called out and (to put it crudely) you lose a lot of status. But on 4Chan, the permission structure is very different. There, making offensive statements and edgy jokes about the supposed inferiority of non-whites is how you gain status, recognition, and praise.

Because we're social animals, permission structures matter a lot.

We've seen the power of permission structures to influence behavior in the last few months. In the aftermath of the presidential election, prominent leftist commentators took to social media and TV to suggest that leftists should reduce contact with their Trump-supporting friends and family members. Yale psychiatrist Amanda Calhoun went on MSNBC to tell leftists that reducing contact with Trump supporters “may be essential for your mental health."

Shortly thereafter, a poll found that 23 percent of leftist respondents planned to spend “less time with certain family members because of their political views.”

I believe that these two phenomena are causally related. When we see prominent people in our tribe telling us that X (in this case, reducing contact with folks across the aisle) is justifiable, we're more likely to do X. In an alternate November-December 2024 in which most leftist influencers took to social media and TV to tell their audience about the importance of bridge-building and of looking past political differences with loved ones, I think this 23 percent number could have been cut in half.

So permission structures matter.

But in that case, why does political violence keep happening? To their immense credit, every politician I follow, and almost every influencer, has used their platform in the past few days to condemn Charlie's murder and to call for a renewed culture of civility.

These calls are important, and I share them. But they also happen every time there's an episode of political violence. In the wake of the attempted assassination of then-candidate Trump, every Democratic politician used their bully pulpit to condemn political violence. Every time there's an act of political violence, every bridge-building organization steps into the breach to encourage us all to be more civil to each other.

Again, I think these calls are vital. I certainly don't want to live in a country in which, for instance, prominent politicians take to the airwaves to egg on violent activists. These calls are probably doing a lot of good.

But while calls like these may be necessary to stop the spread of political violence, they do not seem to be sufficient. Political violence keeps rising.

So what's going on?

As much as we like to talk about one United States of America, from a sociological perspective it's more like we're several different tribes living alongside one another, each with its own permission structure.

I saw this when I was looking at reactions to Charlie's death. In most circles, the murder was universally condemned. That's one permission structure.

But then there were the people who praised or took joy in Charlie's death. There's the X post with 181,000 likes that reads: "Maybe Charlie Kirk shouldn’t have spent years being a hateful demagogic fascist and this wouldn’t have happened. Maybe he should take some personal responsibility." There's the TikTok video (since removed from TikTok) with 55,000 Likes in which the speaker takes palpable joy in Charlie's murder.

In these circles, the permission structure seems to be completely different. In these circles, dancing on Charlie's grave is a route to status and approval.

I think of it like this. Imagine, crudely, that there are two tribes in America. There's Mainstream America, and there's Extremist America.

In Mainstream America, the permission structure says that political violence is never acceptable. In Extremist America, the permission structure says that political violence against folks on the other side is pretty cool, actually.

(Of course, these two tribes actually overlap some, because most of us struggle at least a little bit with humanizing our political opponents. This is a simplified model to illustrate the concept).

Most of the depolarization space, and most mainstream politicians and influencers who condemn political violence, are a part of Mainstream America. They're doing important work in shoring up the permission structure in Mainstream America so that it doesn't become accepting of political violence.

The problem is that all of the violence is coming from Extremist America. This is the tribe where the permission structure valorizes and even encourages political violence, in ways that can push some mentally unwell people over the edge into actual violence.

And Extremist America doesn't care what Mainstream America thinks. The people who gloat about Charlie's death don't care what Barack Obama or Mitt Romney or any centrist bridging organization has to say about political violence.

If we want to end the cycle of violence, I think we have to start reaching the folks in Extremist America.

I think we can do that in two ways.

First, we have to start talking more about political extremism. We have to give extremists' friends and family tools and resources to spot the warning signs and to intervene in a loving and healthy way.

Second, I think (in whatever way that we feel safe doing so) that there's immense value in talking to the extremists themselves.

In The West Wing, President Bartlet is asked to speak after a terrible national tragedy (someone set off a bomb at a college). He said of the perpetrator(s): "I don't know what they want.

All I know for sure, all I know for certain, is that they weren't born wanting to do this."

The extremists in our great country (on both right and left) aren't monsters, and they weren't born wanting to do evil. They're often the people who feel kicked and spat on by society. They feel abandoned and cast out. Many feel humiliated, disconnected, and like they have nothing to really live for.

We can help with that.

We can help these folks to build lives of meaning and purpose.

We can help them to feel seen and heard.

We can extend the loving arms of kindness, so that they don't feel so alone that they're driven into the arms of radical militants.

We can show them how intensely and how deeply God loves them.

I don't know anything about Charlie's murderer. But I know that he wasn't born wanting to kill Charlie. And I pray that, if we can find the wisdom and the courage to reach out to folks like this before they pull the trigger, we can help them to get off of a violent and self-destructive path before it's too late.

Heal the West is 100% reader-supported. If you enjoyed this article, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription or becoming a founding member. I greatly appreciate your support.

Amen!

I’m hoping more people hook up with organizations like Braver Angels so more of us can all get the tools we need to talk to radicals. Because that is WAY easier said than done. Very possible, but those skills need to be taught for most people.

Thank you for your article. It was spot on. I would only add that America needs God. I have certainly myself read way too many posts and seen too many videos of youth that don't see to have any conscience AT ALL. Without an appreciation of the sanctity of human life, I think it is a losing battle for them. Charlie was such an inspiration. When you watch his videos, you can see their faces. It's why they came in droves. They are starving for The Truth. He was one of the only voices out there telling them The Truth. It is up to the rest of us to do it now.