The Dark Side of Safety

I loved writing this piece for Queer Majority. I offer a partial answer to the question, “if our material circumstances are better than they ever have been, why are we all so miserable?” You can find a link to the original here: The Dark Side of Safety

In the United States, we live in an incredibly safe society. Violent crime, while too high if it’s anything but zero, is still extremely low, historically speaking. Data from Statista shows that the rate of violent crime in the United States fell by over 45% from 1990 to 2021. Despite a slight rise in 2020, crime remains far lower than it was just 15 years ago.

As Harvard social scientist Steven Pinker points out in his landmark 2011 book The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, the last 30 years aren't a historical anomaly. Crime of all kinds has steadily fallen over the course of human history. At the same time, a combination of consumer regulations and market forces has, over the past century or so, taken almost all of the danger out of modern life. We work fewer hours than earlier generations in jobs that are generally far less backbreaking. Safety improvements in everything from toys, to food, to automobiles have resulted in far less day-to-day risk for modern Americans relative to what our grandparents would have experienced. Today, we live with a level of physical safety that would have been unimaginable to most of our ancestors. And yet, in spite of this safety, America has produced some of the most fragile people the world has ever seen.

This high level of safety is especially relevant when it comes to LGBT rights. No one can deny that bigotry exists in the US. However, the United States, like much of the West, is far more tolerant of queerness than many other countries. In Barbados (where I used to live), for instance, same-sex relations carried a potential punishment of life in prison up until a few months ago. In Kenya, where I have also lived, so-called "indecent practices between males" can be punished with up to five years' imprisonment. Kenya doesn't enforce the law in every case, but the threat looms over the LGBT community, who have become second-class citizens as a result. This leads to abuses, as Human Rights Watch has documented, of LGBT Kenyans who are often subjected to blackmail, workplace discrimination, and all kinds of violence, because to go to the authorities is to risk arrest.

When I spent a year in college thinking that I might be bisexual and hooking up with guys, I personally encountered occasional prejudice. One of my gay friends was referred to as "it" by bigots on campus. But still, he and I were also lucky to be going through all this in the US, where we knew that jack-booted stormtroopers wouldn't throw me in prison for the supposed crime of kissing another man in a club. This, along with the many other ways in which our lives have been vastly safer than those of previous generations, is unquestionably a good thing — but somehow, we fail to reap the full benefits of decades of progress.

Declining crime rate in the United States from 1990-2021. Source: Statista

In The Coddling of the American Mind (2018), social psychologist Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff, President of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), document how young people are struggling to cope with the (historically light) demands of modern life and adulthood. Having lived their whole lives in environments of ubiquitous safety, more and more students now see mere speech as dangerous and demand that their universities protect them from offensive opinions. According to a study from the Brookings Institution, 53% of undergraduates think that their university should "prohibit certain speech or expression of viewpoints that are offensive or biased against certain groups of people." Stories of students disrupting speakers on campus have become disturbingly common, and these events aren't outliers. The same Brookings survey found that 51% of students apparently feel so threatened by the presence of a speaker on campus with whom they disagree that they support "loudly and repeatedly shouting so that the audience cannot hear the speaker." To a growing number of college students, speech with which they disagree is a form of violence every bit as real and threatening as a punch in the face.

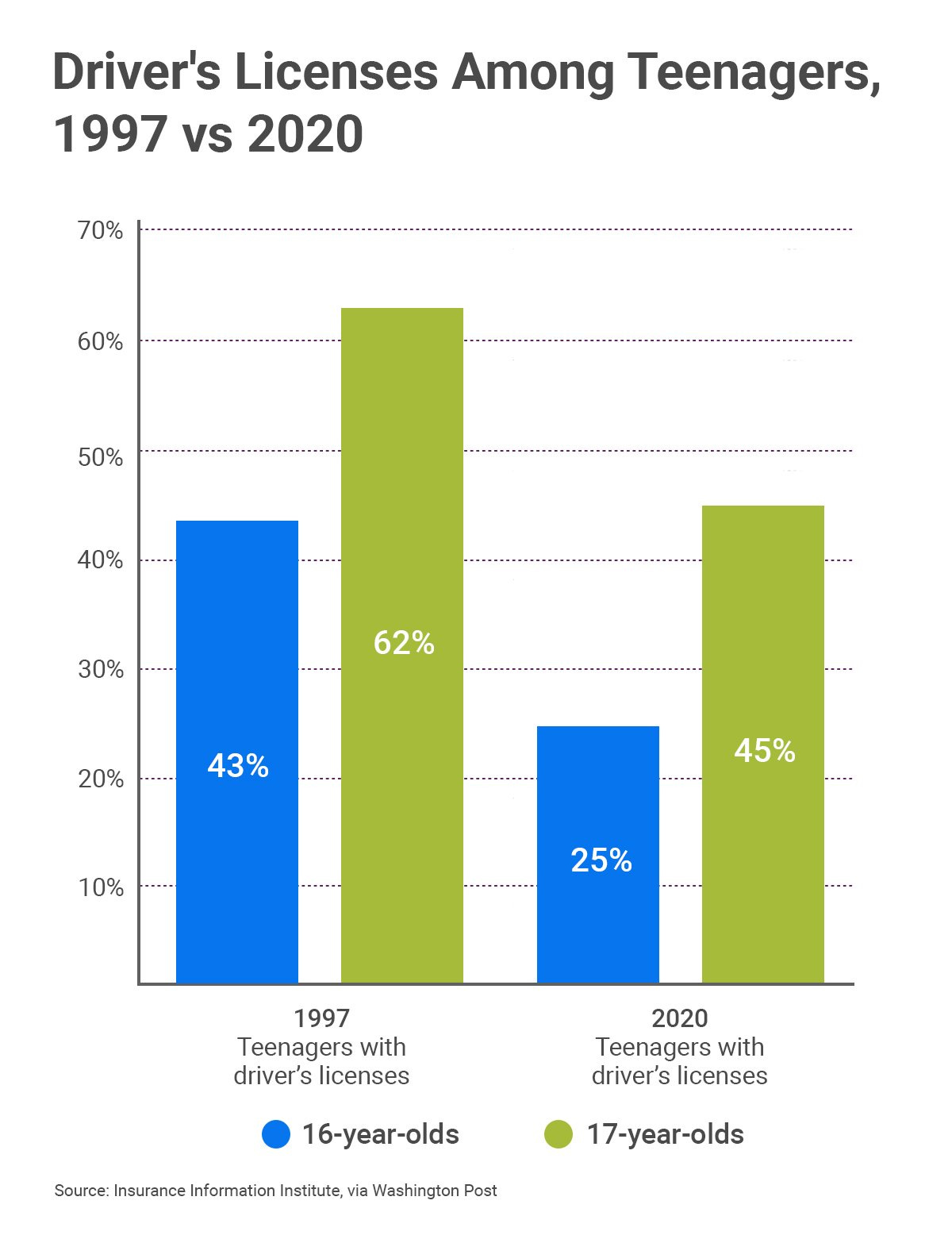

It's not just coping with speech that my generation (I'm 32) finds difficult; many young Americans are having trouble “adulting.” According to data from the Insurance Information Institute, in 1997, 43% of 16-year-olds had driver’s licenses. By 2020, that number had fallen to just 25%. Data from the US Census Bureau shows that younger generations are more likely to live with their parents than prior generations did at the same age. In 2022, 18% of men and 12% of women ages 25 to 34 were living with their parents. A survey from the health insurance company Cigna found that we're even having trouble making friends: "[People born after 1981] are lonelier and claim to be in worse health than older generations." Benchmarks that our grandparents would have sailed past, from getting a driver's license, to living alone, to finding friends, seem to be more difficult for younger Americans.

Source: Washington Post

A major reason for the rise of fragility isn’t safety itself, of course. People don’t need to live under the threat of real violence in order to become resilient. Instead, the cause lies with what Haidt and Lukianoff call “safetyism” — the mindset that safety, especially emotional safety, matters more than anything else. Resilience isn't something that we're born with. Rather, it’s something we build by facing down adversity, large or small. Mental toughness is like physical strength; in order to become strong, we need a significant amount of physical activity. Similarly, we need to experience thousands of challenges, as is the nature of human life, in order to build up the resiliency and emotional muscles to become strong and healthy adults.

For many of us, Western society is so safe that we haven't needed to develop the calluses and skills required to deal with truly difficult problems, like cops threatening to arrest us for our sexuality. It’s a good thing that we no longer have to endure such treatment, but in the absence of many of the hardships people used to face, and the built-up resilience they developed in response to them, we're much more prone to see small problems as large ones. We lack the context of having faced actual dragons, and so we come to regard mildly bothersome chihuahuas as terrifying monsters. We take the gift of hard-won safety and freedom that was established through great sacrifice, and instead of doing something meaningful and beautiful with it, we fill it with hyperbole and fear.

Part and parcel of this trend is the wave of snowplow parenting that has inadvertently robbed many Millennials and Gen Zers of what opportunities remain to develop thicker skin. Some state governments warn parents that it's too dangerous for children to cross the street by themselves until they're 10 years old. Slumber parties and playdates — themselves once mocked as the product of parental micromanagement — are on the decline, and even when they do happen, many parents constantly hover in order to ensure that nobody gets into an argument or gets their feelings hurt. Parenting magazine once cautioned parents to stay close when their school-age children have playdates because "You want to make sure that no one's feelings get too hurt if there's a squabble."

The problem with all of this is that children need independence, risk, and, yes, a little hurt in order to develop into proper adults who can cope with a rough-and-tumble world. As Haidt and Lukianoff note, many parents today are "denying [kids and teens] the thousands of small challenges, risks, and adversities that they need to face on their own in order to become strong and resilient adults."

One particularly pernicious way that snowplow parenting makes children fragile is by depriving them of free play. Free play is educational and constructively formative because it teaches children all sorts of life skills, such as independence and conflict resolution.

According to an article in the Journal of Pediatrics titled “Decline in Independent Activity as a Cause of Decline in Children’s Mental Wellbeing”, "Children who have more opportunities for independent activities are not only happier in the short run, because the activities engender happiness and a sense of competence, but also happier in the long run because independent activities promote the growth of capacities for coping with life’s inevitable stressors." The authors — three child development researchers — note that when kids are allowed to play unsupervised, they learn to cope with the world and develop emotional resilience. When they aren't allowed to play unsupervised and instead have well-meaning adults hovering around them at all times, they fail to develop an internal locus of control and a sense that they're in the driver's seat of their own life. That leaves them more prone to anxiety, depression, and suicidal tendencies.

Another reason that young Americans often seem so fragile is that, too often, the DEI (“diversity, equity, and inclusion”) frameworks that have become so influential in academia actively encourage students to see themselves as though they are made of glass. At the University of Colorado at Boulder, a document produced by the Center for Inclusion and Social Change says that "Choosing to ignore or disrespect someone’s pronouns is not only an act of oppression but can also be considered an act of violence." This is part of a much broader trend. Similarly, the School District of Philadelphia put out a report affirming the idea that "Misgendering trans people is an act of violence." As Assistant Dean of DEI at Carnegie Mellon, in a public letter about transphobia to the university, wrote, “Violence is not limited to physical harm, but includes mental, emotional, psychological, and spiritual harm.” More and more prominent organizations are pushing the idea that simply uttering the wrong words, regardless of intent, is equivalent to physically hurting people.

Many DEI authorities at universities encourage students to see harmful “microaggressions” subtly hidden in the speech of their fellow students. Of course, some students do aim to offend, but they are rarer than these authorities make them out to be. As Haidt and Lukianoff note, all of this can be awful for students' ability to develop mental health and emotional resilience: "Teaching people to see more aggression in ambiguous interactions, take more offense, feel more negative emotions, and avoid questioning their initial interpretations strikes us as unwise, to say the least."

These DEI curricula draw upon a Critical Social Justice (CSJ) worldview that, for all its complaints of false binaries, has a clear fondness for painting people as either oppressors or oppressed. They also have an odd habit of depicting members of so-called "oppressed" groups as a mixture of wise and saintly, while also little better than helpless children. In Is Everyone Really Equal?, a 2012 CSJ textbook for graduate students in education, Robin DiAngelo and Özlem Sensoy list traits that they believe are held by "individual[s] from the DOMINANT GROUP" [sic] in society; for example men, straight people, white people, etc. They contrast these with traits that they believe are held by "individual[s] from the MINORITIZED GROUP" [sic]. DiAngelo and Sensoy argue that the latter group "feels inappropriate, awkward, doesn't trust perception”, “finds it difficult to speak up", and that these people "lack initiative." When authority figures — from university administrators to textbook authors — tell queer students that they are fragile children who cannot cope with the trials and tribulations of life, should we be surprised when students believe them?

The DEI industry, which has spread far beyond education and into the corporate and nonprofit sectors, does more than merely make people less emotionally resilient. Its divisive and unproductive rhetoric alienates large swaths of the public, undermining the liberal principles and once-trusted institutions that have helped enable the rise of safety and decline of violence in the first place. We are sowing the seeds of future turmoil while stripping future generations of the psychological tools needed to deal with it.

So what's the solution? Society may be failing young people, at least in this regard, but that doesn’t mean that we have to fail ourselves. I grew up a scared and tremulous kid, and even in my 20s, I was terrified of the kinds of things that my friends considered normal — where they saw chihuahuas, I saw loathsome dragons.

Once I realized that this was a problem, I started searching for another way. I looked for opportunities to build up my own mental and emotional toughness. I challenged myself by attending dance lessons and forced myself, despite the utter panic and negative self-talk I felt inside, to ask the prettiest girl in the room to dance. I worked out, striving to hit the Navy SEAL fitness guidelines. When traveling to developing countries, I deliberately used what I saw to get over my “first-world problems.” In other words, I embraced the concept of antifragility. What safetyism, snowplow parenting, and growing up in the most sheltered period in human history won't give us in childhood, we can go out and find for ourselves as adults. We just have to be deliberate and conscious.

The second thing that we can do for ourselves is to consciously push back against the increasingly bloated DEI industry and its largely ineffective and even counter-productive offerings. To be clear, I am not arguing against actual diversity or actual inclusion. Sadly, those nice-sounding words have been co-opted by an industry that has been able to thrive and consume huge amounts of resources despite its inability to actually deliver on its promises. I am against DEI’s push for “equity” which, despite rosy depictions thereof, really means letting believers in DEI attempt to socially engineer equal outcomes between groups - all without regard for the diversity that exists between individuals. Actual diversity, actual equality (as opposed to equity), and actual inclusion — the concepts and principles themselves are essential to a liberal and pluralistic democracy. Many groups in the US have received a historically poor seat at the table, and some still do. We must work to fix that. At the same time, many of us are being brainwashed by a dogma that paints us as helpless and marginalized. We're letting this ideology turn us into victims, which is no way to live.

It's important to note that all of these problems — even the problematic DEI industry, which focuses so much on microaggressions because true racism is at historically low levels — are good problems to have. They are byproducts of enormous material and political progress. But progress is not something we can take for granted. It requires constant maintenance. If we do not solve these “luxury problems”, they will, in time, become serious problems. If we can put the effort in to mitigate them, however, and build back our emotional resilience, we can enjoy the best of both worlds: material prosperity and safety along with living far happier and more harmonious lives. We'll also have a lot more capacity to go out there and fight actual oppression, of which humanity is in ample supply. It is every generation’s ideal to leave the world a better place than they found it. If we don’t toughen up, and soon, we will be unable to follow through on that aspiration — and history will not judge us kindly for it.